The city of Vancouver is consistently named among the world’s most desirable places to live. With its picturesque location between English Bay and Mount Baker, the largest city in British Columbia attracts visitors – and new residents – from all over the world.

Indeed, metropolitan Vancouver – the city and its surrounding suburbs – was the 12th fastest-growing region in North America in 2019, according to Canada’s Daily Hive. The region is expected to add nearly 1 million more residents by 2050, according to data used to develop the region’s recently approved 30-year growth plan.

“Here in Vancouver, we’ve had lots and lots of development,” said Phillip White, the city’s Plumbing and Mechanical Inspections manager. “It’s getting very dense.”

But massive development leads to growing pains for any city, especially when it translates to expensive infrastructure fixes. For Vancouver, the issue was what White called “a dirty secret”: insufficient sewer capacity.

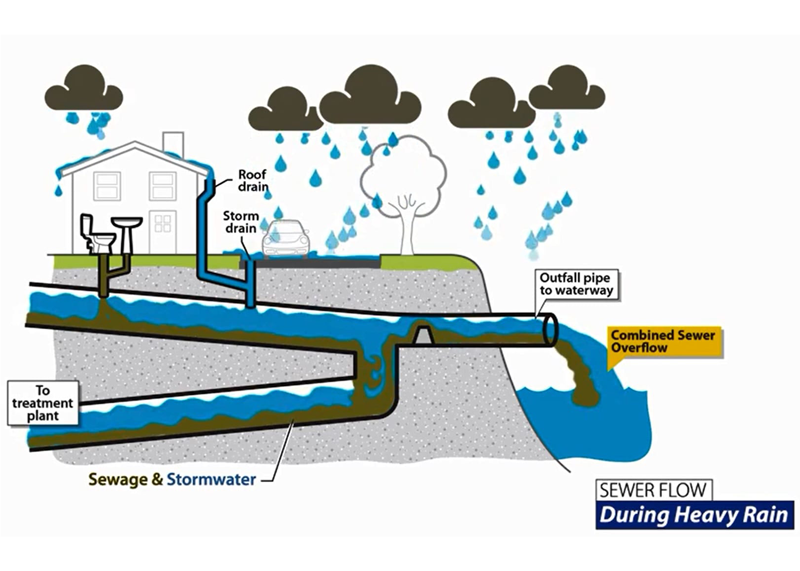

Vancouver uses a Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) system, a wastewater system that collects both stormwater runoff and sanitary sewage in the same pipes.

Water flowing into the combined sewer system can exceed the capacity of the treatment plant during heavy rain or snowmelt. As a result, untreated or partially treated wastewater is discharged directly into nearby rivers, lakes, or streams, causing water pollution that poses health risks to humans and wildlife.

“Up to 10% of the city’s sanitary sewage was discharged as a combined sewer overflow, leading to high levels of contamination in local waterways,” White said. “For the last 50 years, we’ve had sanitary contamination closures of fisheries around local waterways.”

Vancouver is not unique in their wastewater system. About 700 municipalities in the U.S. have CSO systems, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Increasing storage capacity or building separate stormwater and wastewater systems can be costly infrastructure upgrades for municipalities.

White and his team took a different approach in the Greater Vancouver region with a water reuse plan. Their learning can benefit other municipalities seeking to reduce stormwater runoff problems.

What Do We Do with All this Rain? Smart and Safe Water Reuse

White noted that there are only a few ways to keep stormwater out of infrastructure:

- Green roofs can evaporate water, but roof space on buildings can be limited due to mechanical equipment and social areas.

- Water-absorbing landscaping can be a solution, but cities have limited available space to implement it.

- A detention tank can hold back water volumes during rain events but the water still ends up going into the system.

“Non-potable reuse is the best bang for the city,” White said. He cited the ability to use water reuse for toilet flushing and even for use in cooling towers where the water will evaporate.

What Works — And What Doesn’t Work — With Water Reuse

The city of Vancouver started with an evaluation of existing rainwater harvesting systems and found examples of poor design and maintenance, or “handyman work,” in White’s words. There were instances when potable and non-potable water systems were connected directly without backflow prevention to protect against cross-contamination.

White and his team developed new local policies for water reuse in consultation with plumbing industry experts, including IAPMO, which coordinates the development and adaptation of plumbing and mechanical codes to meet the specific needs of individual jurisdictions in North America and abroad.

“Our code went from five sentences to five pages. It’s not bureaucratic in any way,” White said, explaining the benefits of being prescriptive about safe designs and installations.

A trained registered professional must design all new rainwater harvesting systems and use manufactured purple piping when running through dwelling units in multi-unit residential buildings. The purple piping signifies non-potable water to anyone who might go behind the walls in the future for repairs and upgrades.

Pipe sizing is determined using the IAPMO Water Demand Calculator, which saves money on new construction costs and reduces the amount of stagnant water in pipes, minimizing the risk of waterborne illnesses such as Legionella.

“Because most of the sites aren’t adding chlorine to the captured rainwater, we don’t want that water sitting in there too long,” White said. “The more we looked around, the more it made sense to adopt the Water Demand Calculator for non-potable water reuse systems.”

Why Plumbing Codes Need Standardized Customization

As a result, Vancouver is the only city in British Columbia to have its own plumbing code; the rest of the province — except for some federal lands — is governed by the BC Plumbing Code (BCPC), which is modeled after the National Plumbing Code of Canada. Vancouver has combined those codes into one that is unique to the city and best suits its needs.

Plumbing systems are not one-size-fits-all, unlike other building and construction codes and standards. Plumbing codes are a local concern due to variances in regional climate, existing infrastructure, and local water quality, to name a few.

Water reuse systems can benefit rain-heavy cities like Vancouver and drought-plagued areas alike, but there are different considerations for different circumstances.

Vancouver’s innovative approach to managing its insufficient sewer capacity showcases the adaptability and resilience of a city determined to grow sustainably. By implementing a non-potable water reuse plan, Vancouver has not only addressed its immediate infrastructure challenges but also set a precedent for other cities around the world facing similar problems.

As Vancouver continues to thrive and attract new residents, it remains a shining example of how urban centers can harness their unique resources to create a cleaner, greener, and more prosperous future for all.

Cover photo courtesy of Destination Vancouver